Holy Island Monastry Competition

Scotland, 1993

In 1993 I decided to enter a competition for the first time. I won the 4th place and a commendation. It was a competition for a project intended to be built and I was very interested in bringing my work to London, searching for projects in London or in the UK in general. The international competition was a popular one amongst young architects and was run by the RIAS (the Scottish equivalent of the RIBA).

I worked on this competition in collaboration with the structural engineer Neil Thomas, founder of Atelier One, and the environmental engineer Patrick Bellew, the founder of Atelier Ten; at the time they worked together on many projects. I invited them to work with me on this occasion by sending them a black and white postcard of my Tel-Aviv promenade proposal asking if they were interested in collaborating with me; they agreed.

The Holy Island is a 4 km long by less than a kilometre wide mountainous island, located off the coast of Arran in the Firth of Clyde (not very far from Glasgow). The island has a long spiritual history: it is endowed with an ancient healing spring, the hermit-cave of a 6th Century monk, St Molaise, and evidence of a 13th Century Christian monastery. The Tibetan Buddhist centre from Samye Ling was presented this island in 1992 as a gift from a private owner, in order to build a centre for the public and a monastery for the coming millennium. Lama Yeshe was the executive director of The Holy Island Project. Part of the program was to design a monastery for the 21st century: as a spiritual place with an ecological sustainable attitude.

There were three major parts to the complex: a residential territory for the spiritual teacher Lama Yeshe and for his guests who often come with an entourage, and two monasteries, one for monks and one for nuns. Each must include private single rooms - where they would spend their long hours - communal showers and toilets, a praying room, a yoga room, a dining room with a kitchen next to it, washing room and a workshop.

I worked out the project with the aid of a big model (approximately 2 x 2m) by myself, for three months. I made the topography from flat, flexible cork sheets and the buildings from the same white plastic sheets I worked with in the Tel-Aviv promenade project.

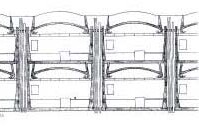

I designed all these facilities around a courtyard, lying along the mountain slopes where the main entrance led to the courtyard in its lower part, not very far from the sea shore, with the kitchen and dining room facing south and the sea. The workshop was the same, including the lower part next to the entrance where the goods arrive from.

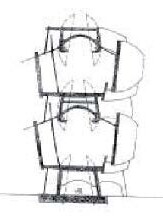

The room layout looked in plan like many hands stretching into the landscape with each ‘hand’ layered in two floors. The monks are there to be in solitude while they spend long hours in a specific ‘sit-box’ in the middle of the room. When they are out of their rooms it is for a scheduled activity within their community and they gather in the bigger communal rooms. Therefore, in each room, the box they would sit in was surrounded by walls with no interruptions, while the openings were continuous windows skirting the point where the walls meet the ceiling, looking on to the sky.

The room layout looked in plan like many hands stretching into the landscape with each ‘hand’ layered in two floors. The monks are there to be in solitude while they spend long hours in a specific ‘sit-box’ in the middle of the room. When they are out of their rooms it is for a scheduled activity within their community and they gather in the bigger communal rooms. Therefore, in each room, the box they would sit in was surrounded by walls with no interruptions, while the openings were continuous windows skirting the point where the walls meet the ceiling, looking on to the sky.

The praying room and the yoga room were located in the upper part of the courtyard, looking onto breathtaking views: down through the open courtyard, into the island and the sea and up toward the peak of the rocky mountain which was covered with pink heather in summer and low shrubs all year long (there were hardly any trees on this island).

The same distinctive walls continued from the monasteries’ courtyards leading towards a gazebo further up on the mountain, towards its peak and distanced from the monastery’s complex. All along the walls, in the courtyard and all the way up to the gazeboes, there were cylinders spinning as part of the walls’ design, using the prevalent strong winds to create the energy source for that complex. These were inspired by a common sight in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in Tibet where cylinders spinning around were connected with the local tradition of symbolising reading scrolls as they were spinning around. The Holy Island monastery was never built.

In terms of aesthetics, I continued with my soft language of flat, long, undisturbed, dynamic white concrete strips. The buildings were designed in such a way that light would come in from between light concrete strips, or between a strip and ceiling or between a strip and the floor. The sky had a big presence in this scheme, with views revealed in between the wall strips with which I framed the sky, the only nature present in the monks’ and nuns’ private rooms, where they spend most of their time. (I was looking at Georgia O’Keefe’s paintings, specifically:Green Grey, 1931, Abstraction, 1926, Pelvis with Moon, 1943, Pelvis I (Pelvis with blue), 1944.

Besides enjoying the fact my project was appreciated was the experience of listening to the comedian Billy Connolly and his hilarious anecdotes about the Tibetan Buddhists and having him presenting me with the award and shaking my hand at the awards giving ceremony.

Visuals and photography by Yael Reisner Studio.