Yael Reisner with Fleur Watson, Architecture and Beauty,

Conversations with Architects about A Troubled Relationship, Wiley, 2010

Yael Reisner on her incentive to interview architects about this troubled relationship between architecture and beauty.

June 2010

How is it that good architecture or brilliant buildings tend to be judged by their capacity to produce an aesthetic experience, yet very often architectural design is neither led by nor generated through a process that is engaged with aesthetical issues or visual thinking?

How is it that personal attitude is still what characterises the modern use of the word aesthetics, but in architecture from the 20th century onwards we find a separation – and often a denial – of any association between architectural aesthetics (its visual quality) and the presence of the Self.

No one questions this basic contradiction, especially not architects. Between 1998 and 2003, as disparate individuals as Glenn Murcutt, Kathryn Findlay, Gaetano Pesce, Winey Maas, Massimiliano Fuksas, Lebbeus Woods and Thom Mayne all added with a certain pride in both lectures and interviews that their architecture has nothing to do with aesthetics. The decades that architects focused on generating architecture through involving their personal attitude, intuitive judgement and emotional input - mainly represented by Art Nouveau, German Expressionism and ‘Deconstructivist’ Architecture (explained in the book) - were historically brief, particularly when compared to the more dominant movements of the 19th and 20th century, where the personal voice was substituted by cerebral voices that were perceived as objective by both Neoclassicism and Modernism. This inclination continued amongst most Digital architects of the last 20 years, whose interest in form-led architecture was linked to a distancing of aesthetics from identity.

The aim of my research was to expose, witness and discuss what I had identified as a ‘troubled relationship’ between architecture and beauty, or architecture and aesthetics, and to challenge what seemed to be a great paradox at the centre of contemporary architectural thinking. Moreover, I believe that aesthetics has the ability to synthesize all of architecture’s complex qualities, emotional values, poetics, pragmatic constraints and overbearing cultural issues, while at the same time yielding good architectural design. With buildings so often trying to reflect local qualities and collective memories, my argument is that one’s intimate landscape is as important as technical knowledge, that the architect’s personal attitude should not be purged in order to assist the architectural process.

The perception of many architects, that their rational being should be the leading faculty in design, stems in part from the connection between aesthetics and subjectivity that was outlined in the word’s definition by Alexander Baumgarten in the 18th century, as a notion of ‘taste’ and a ‘sense of beauty’. It was during the 20th century that Socialism promoted the idea that content is more important than appearance or aesthetics, and there was a growing critique on the hegemony of the eye. Democracy’s Public Opinion replaced individual taste, and architects who saw themselves as serving society elevated objective considerations and suppressed any subjective license. This trust in rational thinking was influenced by the intellectualisation of the thought process in Western society.

The abstraction of visualisation and its cerebral interpretation started in the 15th century with the introduction of script and alphabetic typography and continued with the invention of ‘perspective’ and the increased use of maps to represent the world, culminating in the 20th century with the proliferation of information, where statistical data could become visualised facts, abstracted through diagrams and graphs. Unfortunately such a mentality made many people consider intuitive visual thinking as deprived of intellectual depth. Moreover, trust in exclusively rational approach has been encouraged by scientific revolutions of the last 500 years. However, the scientific process itself has always been involved with intuitive, lateral thinking and infused with personal passions that are often in search of new aesthetics. With architecture, personal insight and emotional input not only has the potential to be visually powerful, but can also contribute to people’s emotional existence. Beauty enhances happiness and delight, but the tendency to consciously ignore emotions and aesthetics ultimately threatens to alienate people’s experience of architecture.

I opted for a set of interviewees from different generations and origin in order to clearly examine how this ‘troubled relationship’ has been perceived through different historical and geo-cultural contexts. The choice was usually architects whose work I found attractive, while not necessarily agreeing with their schools of thought – in essence setting up the possibility of encountering a ‘troubled relationship’ in the work of the architects themselves. There are sixteen interviewees – Frank Gehry, Zvi Hecker, Peter Cook, Juhani Pallasmaa, Lebbeus Woods, Gaetano Pesce, Wolf Prix, Thom Mayne, Eric Moss, Will Alsop, Zaha Hadid, Odile Decq, Mark Goulthorpe, Greg Lynn, Kolatan/MacDonald and Hernan Diaz Alonso – who provide a rich cross section of opinion, and while they collectively represent only a small sample of a potentially large number of architects who could have been included, they are all particularly engaged with issues relevant to those that I aimed to raise through these conversations.

Different questions were presented with different levels of intensity and often depended on the interviewee’s approach to architecture to the extent that there was no need to repeat all the same questions so as to highlight my critique.

I met each of the 16 architects twice and some three times over a period of nearly three years; from early 2004 to 2007. Through the discussions with them an access was provided to the formative experiences, creative processes and motivations of some of the most influential design figures today, capturing their voices, thoughts and personalities.

All interviewees are or have been leading architectural educators and are generally considered mavericks who have moved architecture forward through talent, originality, integrity and individuality. In all the interviews, as the ‘troubled relationship’ between architecture and beauty was considered, the context of both the interviewee’s body of work and their approach to architectural design became important parts of the conversation.

Since the book was released I have been invited to lead six symposiums and numerous lectures and seminars that further investigate this compelling thematic.

And few more notes on An Aesthetic ambition

At the end of the 20th century contemporary visual art stood on the ruins of beauty. Miraculously, architecture is still mostly being judged by its capacity to produce an aesthetic experience, and that is still the case because of the very nature of architecture which results in it being a physical presence. If the appearance is not positively attractive or exciting then it is just a building and not architecture.

Here is the base of my argument: in spite of the ‘form follow function’ attitude and the more inclusive, anti-ocular culture of the 20th century, architecture has to result in an attractive physical presence. The aim of the architect is to ensure that we end up with architecture and not just with buildings, as happens so often during the second half of the 20th century.

My personal ambition as an architect was already clear to me in 1998 and became more so through my teaching at the Bartlett, where I aimed to search for the poetic in architecture - the spirited, the new, the rare, the surprising; all that will have the capacity to touch our senses so as to bring a better, more exciting, environment for living in to our everyday lives. I never found delight in the ‘ordinary’ as we know some others do. The ‘ordinary’ as was celebrated for some years leaves us indifferent: it contains in social classification, boredom, suffering, fear and life hardship. I feel that an ordinary space makes the life inside it, often, meaningless.

For me it lacks relevance in our time right now. I don’t believe in the righteousness of facts, data, and objective analysis since any truth could be manipulated into any set of ‘objectives’: I place personal experience of how we interpret the world at the root of the creative process, producing work that would be the closest to my genuine judgments.

Personal expression and visual perception in architecture

Contemporary architectural discourses and processes of practice are widely anchored in some, if not all, of the following conditions: climate, location, client, program, energy-economizing, functional considerations, purpose, statistics, commerce, principles of structure, materials, building technology…and probably others besides. Each of these discourses is considered (together and separately) by many as the sum content of architectural practice; in my opinion, this is not the case.

Architecture often falls into the trap of focusing solely on content, while in matters of the visual expression of such content the conversation remains meagre and simplistic. Susan Sontang explains in her book Against Interpretation, as part of the discussion of abstract art in the sixties, that ever since Ancient Greece, when Plato and Aristotle discussed theories of art as imitation - ’mimesis‘ - and representation, art has been perceived as verbal, discourse-based content rather than its form, out of an assumption that the work of art is its content and form is only a side-effect.

All the accompanying contents I have just listed probably constitute an integral part of the architectural act, and they most probably affect the architectural practice, but they do not necessarily testify to the nature of a specific architect or to his/her architectural language. That tendency goes hand-in-hand with the architects’ reluctance, which we often witness, to admit any genuine involvement with aesthetic considerations. Architectural design is an act of bringing together rational and irrational, objective and subjective, components.

As summarized and clarified by Mordechay Geldman, regarding the world of art, in his book Dark Mirror:

“In any case, clearly there is an Otherness – both actual and potential, nesting beyond the images of the self that are created by powerful social conditionings, seeking to dominate the subject’s body and soul. In the absence of any contact with this Otherness, the personality dies behind a forced mask, it becomes a mechanical-robotic shell, reciting collective texts and seeing only what it is ordered to see” Mordechai Geldman, A Dark Mirror, Essays, Hakibbutz Hameuchad, Publishing House,1995. (published in Hebrew)

As long as we do not adopt personal expression into the world of the architectural entity, we will continue to recite collective texts.

In the course of the twentieth century, with regularity, in cycles of interest that recur with vigour (though each time slightly differently), deep and fundamental hostility manifests itself towards anything that bears any sign of ‘subjective’ elements in architecture, as I discussed already in the different chapters. Architects, more often than not, are paradoxically living in conflict with the world around them; we a live in a world that strives to become more pluralistic and tolerant than ever before, where the individual has the possibility of personal expression and the right to ‘Otherness’. The architect’s complex (i.e. fear of engaging with the personal) leads to confusion and to a distortion of the essence of architecture. Recognition of this conflict, its sources and implications, sheds light, among other things, on the way in which we must train new generations to this activity.

One way to attain culture diversity in architecture, and to develop authentic and unique local culture, is by nurturing and preserving the variance between architects and encouraging them to assimilate the various shades of their personality and culture in their design work, consistently and continuously. Their personal touch has to be manifested in their work. In the various visual qualities of every work of design we must discern personal language and line, from the very first sketches. This approach will enable the uniqueness of each architect to develop and to express itself, and through it the character of the community or the society in which he/she works will also be manifested, since the individual does not live in a social-cultural vacuum.

It is of great importance to be in control of two aspects: to create an affinity between the visual expression of the material that describes our design work and the conceptual content, and to provide a personal line that is manifested in the design product. These elements of the architect’s work are not ‘graphic fashions‘, which they are often underestimated as, but rather, they are an expression of a professional ability, which leads to a deepening of the architectural design. In London, in particular, the tradition of architectural communication culture has developed for decades, alongside the development of the documents through which architecture is lived, breathed and built.

Many architects have the ability to think laterally, to relate between various disciplines, worlds that seem to be unconnected, distant practice ends, and to attain a deep understanding of different phenomena or events. This requires a wide education, culture, an understanding of the details and of the society in which we live, intuition and talent.

Our general education and knowledge is topped up by our understanding of what our domain is about and further more what our personal exclusive areas of knowledge are; our cultural capital.

It is then that the most important aspect of the architect springs into action – his ability to react with an architectural design and event in a manner that summarises his cultural entity and enfolds within it his complex architectural activity: here we have to be the experts.

The book’s chapters:

Introduction - The Genesis of the book by Yael Reisner

Frank Gehry –A White Canvas Moment

Zvi Hecker – A Rare Achievement

Peter Cook – Architecture as Layered Theatre

Juhani Pallasmaa – Beauty is Anchored in Human Life

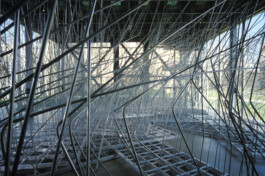

Lebbeus Woods - Heroic Imperfection (click to read)

Gaetano Pesce – Unfettered Maverick (click to read)

Wolf D. Prix , Coop-Himmelb[l]au – Self Confident Forms

Thom Mayne, Morphosis – Exquisite Complexity

Eric O. Moss –The Gnostic Voice

Will Alsop –Pursuit of Pleasure

Zaha Hadid – Planetary Architecture

Odile Decq , ODBC – Black as a Counterpoint

Mark Goulthorpe, dECOi – Indifferent Beauty

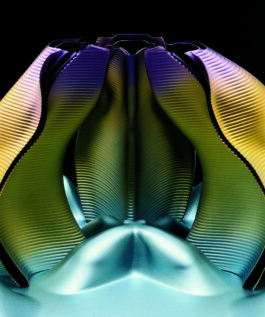

Greg Lynn, Greg Lynn Form – Technique Language and Form

Kolatan MacDonald, KolMac LLC – Creative Impurities

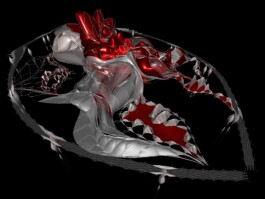

Hernan D. Alonso, Xefirotarch – Digital Virtuosity

Translated to Chinese in 2014 and published as a paperback.

About the book’s reviews:

In ‘The Independent’ Jay Merrick wrote: Why don't today's architects embrace the sublime? That's the thesis of a provocative new book...The troubled relationship between architecture and beauty is being re-exposed at just the right moment...

At the book review in ‘ArchNewsNow.com’ Norman Weinstein wrote: ...Troubled relationship with beauty? What understatement!.. [Reisner] prefaces each interview with something akin to X-ray vision... This might be the most gripping and readable assortment of revealing interviews with starchitects ever published... I can’t imagine a more provocative recent publication architecture students would profit from...

Lebbeus woods at the review in his blog wrote: The cast of characters is mostly familiar ... Yet the new book stands out from routine compendia about contemporary architecture, because of its probing texts about the architects and their work... offering critical evaluations altogether lacking today in most architecture books... This fascinating book sets out to give us plenty to think about, and so it does. The well-written and unpretentious essays peer into the thoughts, aspirations, and, occasionally, even methods of the architects...

Graham Burn at the ‘Building Design’ wrote: ...Reisner’s intelligent selection of architects from all schools of thought might just be the starting point for quite a thrilling, and timely, debate questioning the future of architecture, beauty and content.

Marcus Cruz’s book review, 2010

Yael Reisner with Fleur Watson, Architecture and Beauty, Conversations with Architects about a Troubled Relationship, Wiley 2010

Reviewed by Dr. Marcos Cruz, the Director of the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL, where he is also a Reader and Studio Master of Diploma/MArch Unit 20.

This remarkable document makes a major contribution to a much-needed discussion in contemporary architecture and is truly pertinent. By identifying a ‘troubled relationship’ between architecture and the concept of beauty, Reisner calls attention to the lack of a wider aesthetic debate that embraces more subjective values in architecture.

Reisner does not write this book with the pretention of being an historian, but rather assumes her position as a designer by declaring her own bias towards a position in which ‘aesthetics has the ability to synthesize all of architecture’s complex qualities, emotional values, poetics, pragmatic constraints and overbearing cultural issues, while at the same time yielding good architectural design’; as she argues further, that ‘one’s intimate landscape is as important as technical knowledge, [and] that the architect’s personal attitude should not be purged in order to assist the architectural process.’ This approach clearly distinguishes Architecture and Beauty from other books. Reisner is able to draw from the interviews not just frank discussions about this ‘troubled relationship’, but also new insights into the architect’s own work, which is well documented through a great set of illustrations.

The book is the result of a great deal of commitment. I know how much effort it required to secure several interviews with such prominent architects. This allowed Reisner’s conversations to develop over time naturally, guaranteeing both interviewer and interviewee an accurate and more in-depth understanding of one another’s individual positions. In this context, I find the division of the book into a main text (which has a very accessible way of writing), captions (which refer more to the projects) and footnotes (which are full of fascinating details) very helpful and well structured.

Reisner deliberately chose a variety of architects whose work is unquestionably of great importance today, and whose responses embrace an even broader range of attitudes and approaches than she expected on the onset. Rather than questioning her selection for this book, I would rather suggest that a second volume with another set of interviewees be produced to broaden the scope of this discussion further still. A series of these books could become an extraordinary testimony of our contemporary architecture.

I cannot stress more the importance of this work, and the rigour with which Reisner has articulated a debate which is wide open and hopefully just about to regain a new weight in contemporary architecture.